When you have a leak in your house, a termite infestation, or a car breaks down, you usually call for help. In dealing with complex problems, we often defer to experts. The risk-benefit analysis of trying to fix a faulty mechanism that is out of our area of understanding is pretty one-sided.

The Political mechanism

Let’s define politics as a country’s system of allocating resources and more broadly – resolving conflicting interests among the citizenry.

Who are political experts?

Democracy gives power to the people, an equal right for each person to determine the path the country will take. In effect, every single one of us is the “Political expert”, but not everyone is qualified to consider and tinker with delicate, multi-faceted systems.

The expert’s expert

De facto, thought leaders and politicians, philosophers, and activists, emerge as the “real” experts which we defer to. In theory, we should have a rational choice based on the arguments laid out by those experts. In practice, we see democracies trending towards a stalemate between 2 large political camps. It could be that every democracy is faced with truly equivalent ideologies, but let’s suggest a different explanation.

The car isn’t breaking down, but the seating arrangement is unfair

What do we know about public policy before an election in an industrialized democratic country?

- Safe: keeps the vast majority alive

- Provides: people manage to work and provide for themselves

- Works: this system has worked over time

Now we come to an election, supposing all the prerequisites are present, let’s draw out a hypothetical and set some terms:

Car – The country, as a political system for people to organize

Destination – Goals which could be general and specific

Occupants – Political parties

Tribe members– citizens of the country, represented by the car.

Route – a series of steps to reach a destination

Driver – The party in control of where the country is headed.

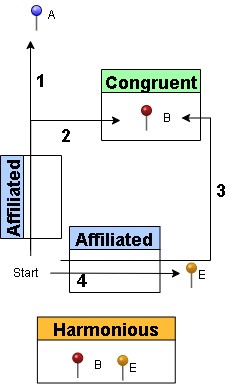

Affiliation – How closely correlated the occupants’ routes are to each other:

- Interfering

- Neutral

- Similar

- Same

Congruity – How closely the occupants’ destinations are to each other.

Harmonious – How complementary or interfering destinations are.

We’ll describe a parliamentary democracy but will quickly see how this dynamic structure applies to all political organizations on all levels.

Multi-Party Democracy

Let’s first simulate a multi-party democracy

Starting positions: 5 parties, position (i)

A study was conducted in the tribe to send a representative of each group (larger than 5%). The representatives were each allocated seats according to the respective part of the tribe they represent.

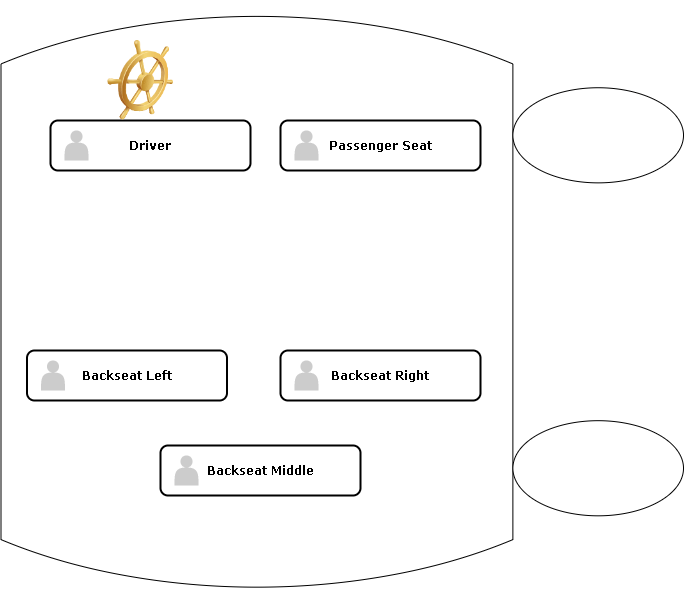

The seat ranking is as follows, best to worst:

- Driver

- Passenger Seat

- Backseat Left, Backseat Right

- Backseat Middle

A – The Driver

B – The Passenger Seat

C – The Backseat Left

D – The Backseat Right

E – The Backseat Middle

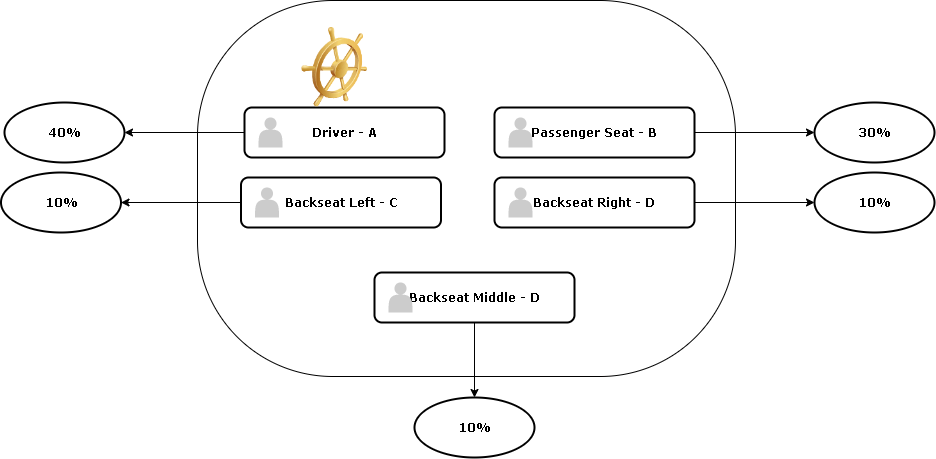

A and B are the largest parties, A with 40%, B with 30%, while C,D, E each represent 10%.

The Ride

Only 50% is required to control the vehicle and so Party A naturally has the most sway over it’s direction, in fact we can see a rule forming:

Rule 1

If in position (i)

- The biggest party + The smallest party > 50%

and

- The 2nd biggest party + The smallest party < 50%

and

- All parties are “affiliation neutral”

then

- Position (i) is equivalent to any position where the biggest party controls more than half (>50%)

Affiliation

The last assumption we made for Rule #1 was neutral affiliation. Affiliation is the similarity of routes to one another. Power politics are influenced by affiliation, which I’ll explore next time.

Leave a comment