The current judicial system reform proposed in Israel sits at a juncture of a number of biases, for some looks like an attempt to destroy democracy, and for others, it is a long due reform opposed by the old elites. I’ll show how the broad democratic narrative emerged, when and why states adopted it, and try to see how successful is democracy when implemented. I’ll show that democracy is not only uncertain, it is also fallible.

Then I’ll try to show the ways in which liberal democracy is similar to organized religion. Democracy as a religion might give an insight into a better way to handle public discourse and decision-making in democracies. Based on this analysis of democracy as a false Consensus, I’ll attempt to show how it may be more useful to look at liberal democracy as a religion that experiences a period of reform and splitting of sects.

Democratic History

Democracy is good… right?

I find this bias extremely fascinating especially when it comes to democracy since a main democratic tenet is pluralism. Pluralism acknowledges that people have different ideas and that there’s legitimacy to most of them. When ideas are shared within the populous certain assumptions lay hidden and unspoken, guardrails for a seemingly open dialogue. When these guardrails are disregarded the resulting speech is considered radical or in our case – undemocratic. What are the reasons that rational, often secular societies, treat a political structure or ideology with an almost holy reverence?

Democratic values have, over the years, gained an aura of purity and divine goodness. When we oppose a political idea or structure, we may try and label it as undemocratic, a toxic label for an idea or an opinion since it goes again our perception of democracy as a pure good. Undemocratic labels take many forms, among which are: fascist, socialist, communist, authoritarian, Orwellian, feudalistic, nazi, anarchist, monarchic, and so on. Could the power of these toxic labels hide the actual problems of representative democracy and give power to groups that aim to obliterate democracy rather than address the problems?

The good guys are democratic, sort of.

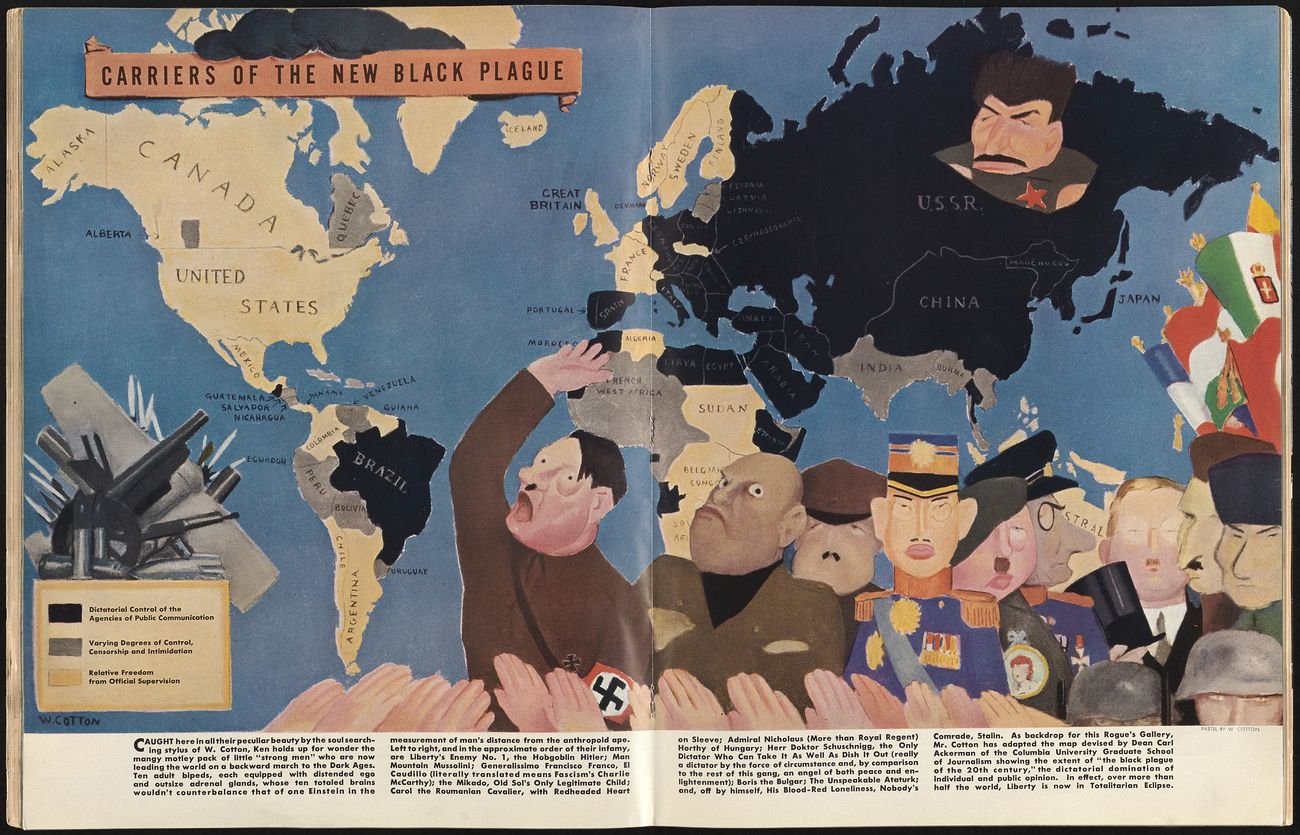

As humans, we have a tendency to see the present situation as permanent. The last imminent existential threat to democracy ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union which never materialized in the form of open conflict and is, therefore, less memorable and impactful than World War 2. The second world war was turned in the western narrative as the battle between good and evil, ending in a democratic allied victory. This depiction is obviously ignoring the crucial alliance with the Soviet Union which suffered the largest number of casualties during the war and was in no way imaginable democratic.

The reliance on Stalin is a big blow to the narrative but not the only one, what about Britain’s empire? in 1939 Britain was a country ruling about a quarter of the world’s population without consent. Just to put this into perspective, around 48 million Britons ruled around 487 million people in the colonies, making it so people choosing the leadership were 8.8% of the empire’s population. In comparison, the Nazi party had 5.8 million members out of a population of around 86 million people (including annexed Austria and occupied Czech territories) which put them at around 6.7%, and by the end of the war Nazi party membership among germans would stand at around 10%. So in terms of representation, the British could hardly claim to clearly be more democratic.

France forgot to give women the right to vote until 1944, Belgium continued its brutally exploiting the Congolese until the 1960s and the US legally abolished slavery but didn’t effectively end racial disenfranchisement of black voters until the 1960s. Judging by our present-day standards, almost no allied country was a free, full, and open democracy. Nevertheless, the narrative stands firm because in the aftermath of the war, the choice was between the 2 major powers (US and USSR), and countries were looking to avoid being occupied again and so sought democracy. Those who fell behind “The Iron Curtain” did suffer under a foreign, corrupt, and brutal regime. After the fall of the USSR, the entire world’s economic system was left in the hands of the United States. There was no viable alternative to becoming a free market, capitalistic, liberal democracy.

And so, Fukuyama wrote his piece, the world went to bed knowing that history ended and liberal democracy won. Wouldn’t that have been nice?

Democracy: what is it good for?

Post-war political default

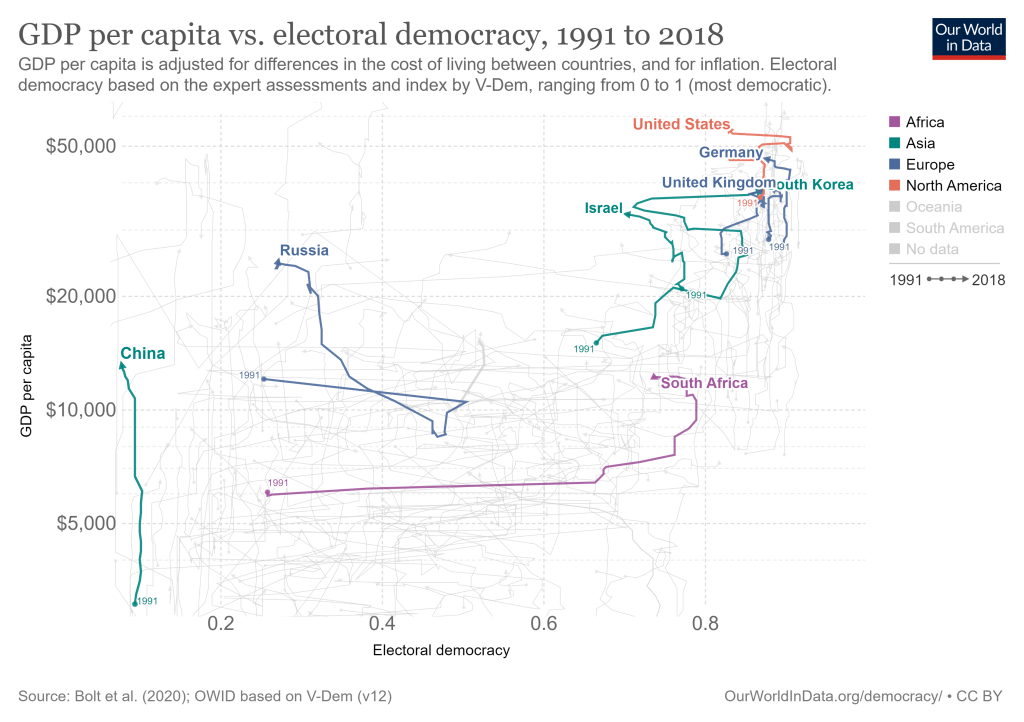

I find this graph depicting GDP per capita in relation to a democracy score interesting. These are just a few countries but we can see that becoming more democratic doesn’t automatically bring increased prosperity and becoming less democratic doesn’t preclude you from economic improvement.

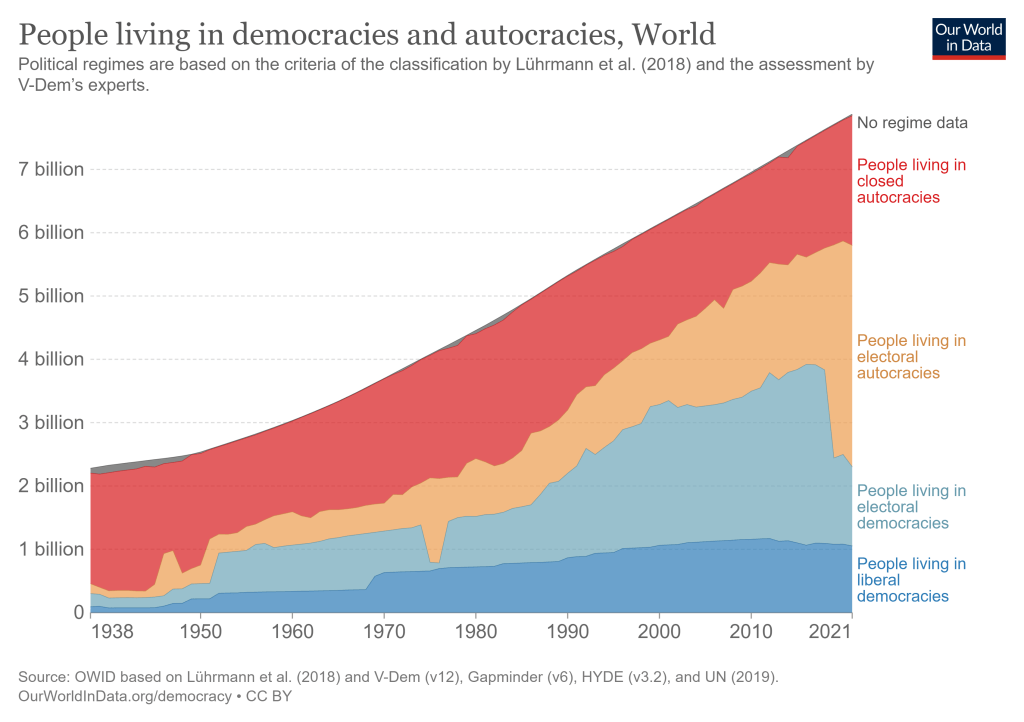

Here we see that the post-war spike in electoral democracies, then a gradual build-up of democratic power across the globe until another rise following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since the 1990s the nations have grappled with democracy, with it being virtually the only game in town, and bumped up against its limits. Is the world backsliding into authoritarianism once again or is democracy evolving and developing other, non-liberal strains?

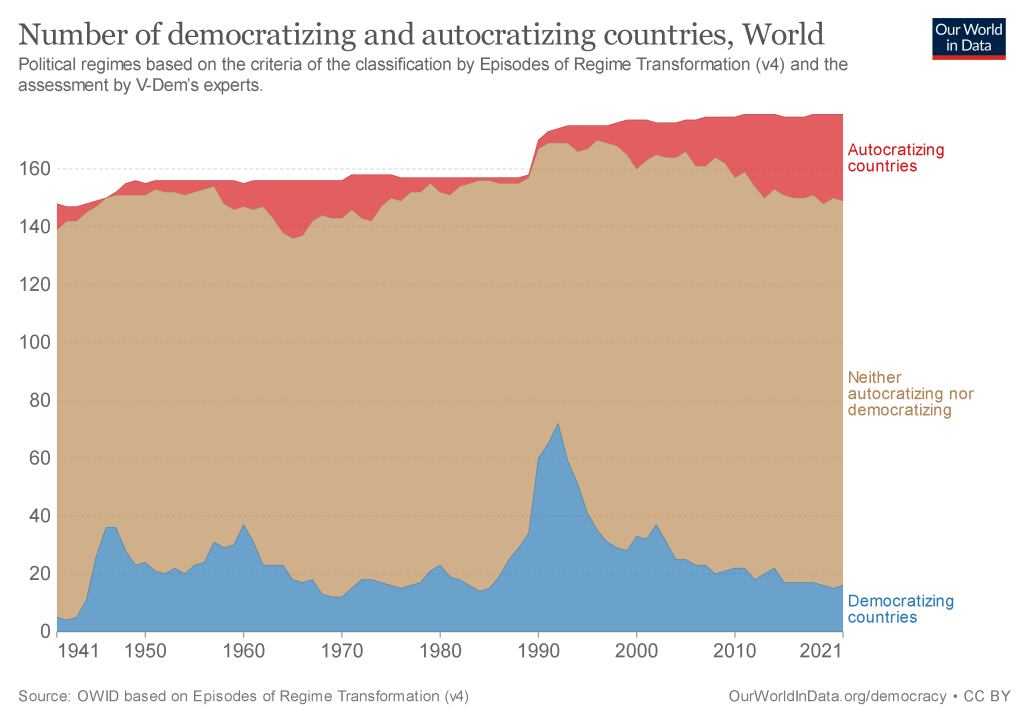

Here we see again the spike in the number of countries adopting democracy in the post-war period and struggling to keep it during the 2nd half of the 20th century. Then, American hegemony in the 1990s brings a major economic incentive and powerful backing for a renewed wave of democratization. Today’s diminishing number of full, liberal democracies is the evolution of other political strains – defying the liberal democratic dogma.

Liberal democracy as a religion

So it seems that democracy isn’t uniformly accepted nor do higher degrees of democratization bring positive economic outcomes. Instead of seeing current events as a struggle between the defenders of democracy and those who seek to destroy it, maybe it would be more substantive to view these sides as factions in a splitting religion in need of reform.

I’ll use the work of Ninian Smart to examine how democracies take the shape of a non-theistic religion, and how the recent decrease in full, liberal democracies mostly indicates a fractioning of this religion rather than people and countries “converting” to another religion.

Smart maps 7 dimensions of religions:

- Narrative/mythological

- Doctrinal

- Ethical

- Institutional

- Material

- Ritual

- Experiential

Narrative Dimension: Democracy as a savior

The modern world is led, economically and scientifically, by democratic powers. Since the resurgence of democracy during the french revolution, it seems like democracy has triumphed in the face of all challenges and led those who stuck with it to prosperity, security, and success. The colonies gained Independence from a king and became the strongest nation on earth, Europeans were also early to adopt democracy and now they’re the most developed continent in the world. Democratic nations stood the test of time against kingdoms, dictatorships, fascists, and communists. Or did they?

Doctrinal: Natural Rights

The enlightenment brought a scientific view of the world and by extension human society. Thinkers such as Voltaire, Montesquieu, and Rousseau were seen as prophets, laying out rules of existing natural law. The democratic liberal dogma they preached included concepts like:

- Seperation of Powers

- Natural Rights

- Equality

- Freedoms of: Assembly, Speech, Religion, etc.

- Rule of Law

This doctrine was about to be supported by a new church, a strong institution to back up its validity and in time, spread it around the world.

Institutionalism: The American Church

The first modern country to adopt a democratic regime was the United States of America. Its founders were deeply influenced by enlightenment thinkers of the time and made sure to engrave democratic tenets into its constitution from the beginning. One could argue that it was a very flawed democracy with representation lacking for slaves and women, and an electoral college system that was designed with little trust in the people’s choice. Nevertheless, we can see a true paradigm shift when Thomas Jefferson writes in the proclamation of Independence the following words:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

– Declaration of Independence, July 4th, 1776

And so, a religious doctrine became the founding principle of a new nation – all men are equal, and therefore, all men have rights and can participate in governing. It wouldn’t be a stretch to call the United States government a church of liberal democracy, setting the benchmark against which other countries measure themselves.

Ethical: : Democracy is fair and just

The Global Democracy Index assigns countries to a category based on their score, they can be a full democracy, a flawed democracy, a hybrid regime, or an authoritarian regime. As residents of democracies who grew up on a triumphant democracy narrative, we are fully aware that democracy exists on a spectrum but often attribute a positive feeling to a change towards “full democracy” and a negative feeling to a change away from it. This heuristic is rooted in our historical, economic, and philosophical perceptions of democracy as a just and practical political structure.

The narrative imbues us with the innate ethical inclination to let people make bad mistakes and fail, suffer from inefficiency, and even jeopardize their safety rather than give control of their fates to a third party. The invisible, intangible rights are found in the doctrine and enforced by institutions to build a moral and ethical framework that values individual freedom over safety and equity. This creates a system where it could be considered morally acceptable to let a person endanger themselves if they choose to do so, and morally reprehensible to take that choice away from them.

The American system employs jury trials that gives ordinary memebrs of a community the right and sacred privilege to decide the legal outcome of a trial. The jury isn’t comprised of legal experts or moral philosophers yet the fate of a person lies in their hands, such dictates a belief that all opinions and judgments should be heard when making a decision. The American system also elects judges, prosecutors and sherrifs, believing the people rather than experts can assess and decide the proper people for the job.

Ritual: Participatory Democracy

In the west, we experience the liberal democratic religion in all facets of life. News media we might consume show us the latest happenings while prioritizing threats to liberal democracy, including foreign and domestic violations of civil liberties and freedoms. The money we use each day often bears the image of a political figure, an important philosopher, or a symbol, all compatible with Liberal Democracy and especially with individual freedom. We pay taxes which symbolizes the consent of the governed, supporting the democratic nation financially. We sign petitions, donate to charities and political organizations, protest, and vote because we believe in our ability to influence the society we live in, reinforced by the democratic system which ensures every person has a voice. These rituals have clear rules and the religious zealotry among differing sides is visible and clear.

Material: The Temples of Washington

If the United States is the birthplace of liberal democracy, then it’s fitting that the high temples lay in Washington D.C., its capital. The city is filled with places of worship to democracy: The U.S. Supreme Court, the National Archives, Congress, The White House, and countless museums and monuments dedicated to certain aspects of the liberal democratic religion. The classical architecture echoes the Roman republic and Greek temples, hiding within their sacred halls ancient texts like the constitution. People from all around the nation and the world doing pilgrimages to the Washington Monument or the Lincoln memorial as major champions of democratic values.

Experiential: “All men are created equal”

The belief that all men were created equal was taken wholesale from the monotheistic religions, with the validity of it assured to us by philosophers and not backed by the divine. Religion serves people with a strong sense of community, unity, and shared values, and Liberal democracy is no different. While there are plenty of opinions about interpretations of democratic values and their hierarchy, only rarely are the values themselves called into question. We feel protected by the rule of Law, we feel free to express ourselves, and feel unity with a large group not based on ethnicity but based on a shared religion that emphasizes our natural rights. We align ourselves with political groups based on our perception of an ideal liberal democracy, usually formed based on communications made by scholars and politicians. Most people’s political affiliations aren’t a result of a deep study of human society but rather a way to identify with a religious sect.

The false consensus

People tend to assume their views and beliefs are more widely held than they actually are. Since the interpretation of democratic values is relatively rare in our daily lives, these different opinions don’t clash visibly. But since the end of the cold war, there is more and more friction within the democratic religion. Differences that were irrelevant in the face of an entirely different value system now surface and sit at the heart of the political controversy in democratic nations. We all think we know what democracy means but looking at democracy as an organized religion raises serious questions. is democracy really a fair and beneficial system? should it be reformed or updated? and if so, how should we test the proposed changes?

Conclusion

Democracy isn’t holy and is different from theistic religions that rely on divine rules, but in practice, much of the public discourse and personal political views take a religious shape. Liberal American democracy saw a massive rise in popularity throughout the 20th century and is now the dominant political religion. The next challenge for the democratic religion seems to come from within, different populist factions and sects seek to either reform the church of democracy or split from it. It might be helpful to keep in mind that many of the believers in those factions truly believe that a different form of democracy will be better. No one side holds the ultimate truth and systematic changes should be possible and discussed in good faith.

Leave a reply to Gallem Cancel reply